Steinway’s Model D: The iconic concert grand piano of choice

Steinway’s Model D: The iconic concert grand piano of choice

by Stephen N. Reed

When Steinway & Sons rolled out their very first Model D concert grand piano in 1884, they could not have known how much one piano model would come to define their company. Top Steinway dealers like M. Steinert & Sons proudly offered this exceptionally designed concert grand then and have been doing so ever since.

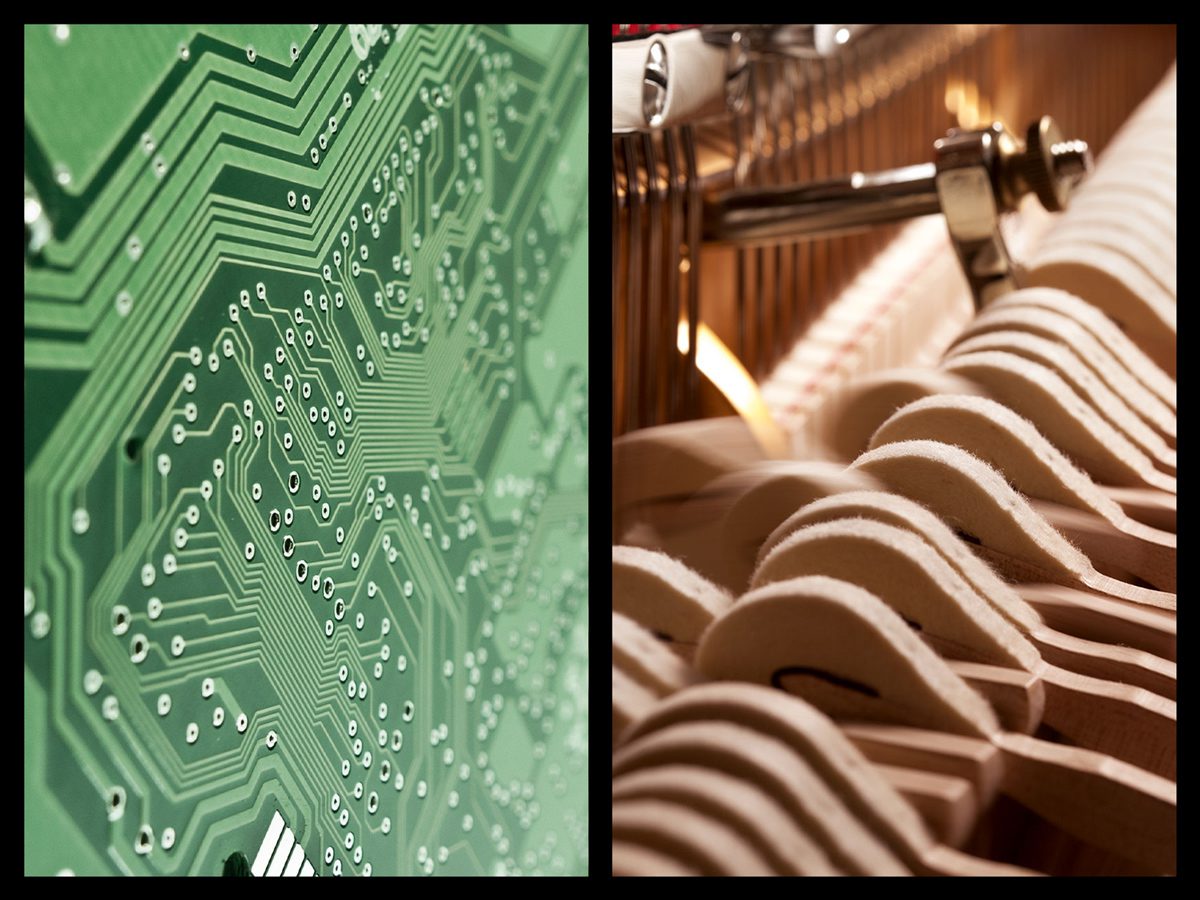

The 130+ piano patents Steinway has filed over the years, along with the best materials and painstaking design features account for much of the Model D’s success.

So does Steinway’s willingness to listen well to the many Steinway Artists who have weighed in over the years on the reasons the nearly 9’ Model D is their concert grand piano of choice.

Hearing these artists’ perspectives provides a better understanding as to why the Model D is preferred by over 95% of professional pianists playing with orchestras worldwide.

The Steinway Model D is so ubiquitous on the major concert stages worldwide that many critics find it synonymous with the word “piano.”

Indeed, the Model D gets to the heart of Padua’s Bartolomeo Cristofori’s breakthrough when creating the first pianoforte in 1700: the ability to bring out greatly diverse shades of loud and soft tones, along with rich colors in both the treble and bass registers.

The Model D is the official piano of hundreds of musical venues, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Juilliard, and the New England Conservatory.

Over 200 colleges and universities are officially designated as All-Steinway Schools, with the Model D taking center stage on their campus’s performing arts centers and music departments.

Moreover, if you’ve listened to a classical or jazz piano recording lately, chances are that you were listening to a Steinway Model D.

Steinway’s competitors point to the competent marketing department at the New York-based piano maker as the key to the Model D’s dominance as the concert grand piano of choice for most performing pianists.

However, such reasoning ignores the stated professional needs of many performing artists who make their living from the musical instrument they play.

Additionally, would institutions of higher education and symphony orchestras risk turning off talented prospective students or season ticket holders with a concert grand piano that didn’t deliver?

What is it that has made the Model D the standard in the industry for generations?

Model D Origins

Early prototypes

Early in the history of Steinway & Sons, one can see the gradual emergence of the concert grand piano that would become the Model D. Some point to the Centennial Grand, rolled out by Steinway in 1875, as the direct precursor to the Model D, which made its appearance in 1884.

But even before the Centennial Grand, elements of the Model D were coming into focus. For example, Steinway’s “Plain Grand Style 2” piano, unveiled in 1868, was already getting closer to 9’ in length and was the first piano with 88 keys.

The Plain Grand Style 2 was Steinway’s lead model and featured Steinway’s patented repeating action and resonator. Stylish appointments included serpentine piano legs.

By the time the Plain Grand Style 2 was built, Steinway & Sons had become the top piano manufacturer in America, with great influence in their industry. Steinway’s use of a cast iron frame and overstringing in the Plain Grand Style 2 were picked up by other piano makers.

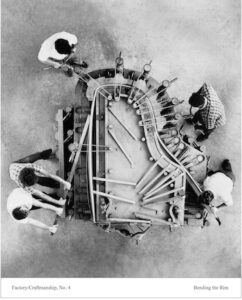

Adapting the first modern rim case

By 1880, Steinway started to produce their Model A, a smaller grand piano that nevertheless had significant ramifications for the Model D later.

Steinway’s Model A featured a laminated maple cabinet, resulting in their first modern rim case. This case was created by the use of long, thin planks of maple that were bent around a form and pressed together with glue.

The result was a stronger and more stable case for the Model A. Steinway had hit upon an approach to their smaller grand pianos’ rims that worked for larger models like the Model D, as well.

The 1884 rollout featured a richer bass for the new Model D

A Model D prototype was used in 1883 as a concert instrument at Steinway Hall in New York City. Steinway then unveiled the 1884 ‘D’, a new concert grand model with a 20-note bass register (instead of 17), a capo bar in both upper treble sections, a multi-laminated case, and a pedal lyre.

Added length brings power and more expression

The modern Model D measures 8’11¾“ in length, an evolution from its earlier prototype which was 8 ½’ in length.

Making the Model D nearly 9’ in length was a deliberate move by Steinway engineers to provide the pianist more control and a wider range of expression, due to the pianist playing back on these longer keys more easily.

Additionally, the length of the keys gives added power for the piano to hold its own with any orchestra–and to be heard well on the back row of any concert hall.

A new, patented soundboard

Except for the Model D lengthening to nearly 9 ‘, few changes occurred in the years that followed, except for a new soundboard.

In 1936, a patented Steinway soundboard was added. This soundboard had a thickened center point that tapers to its edges to yield a quicker response and longevity.

The combination of the stronger rim, a richer bass, and a patented Steinway soundboard has been to create a Model D concert grand piano that now constitutes 5% of all Steinway grands created each year. All of Steinway’s famous piano innovations come together in this one concert-level instrument.

Since 2010, 25,000 of the 600,000 pianos built by Steinway have been Model Ds. Of the 424 Centennial Grand predecessor pianos, about 30 still exist.

Tone, timbre, and touch: What the Model D gets right

A broad tone and a spine-tingling timbre

Steinway’s commitment to establishing a strong bass register back in 1884 has paid big dividends over the years. Over the years, the Model D and other Steinway grands have possessed a strong bass to go along with their broad tone and a timbre some have called “spine-tingling.”

The sheer power in a Model D allows it to project to the back of any concert hall.

The Model D’s touch: A highly-responsive action with longer keys

The Model D’s action is exceptionally responsive, allowing the pianist to channel a range of subtle emotions directly into the keyboard. Again, the length of the keys in the Model D is responsible. The pianist utilizes their gentler feel when playing towards the back of the keys.

This sophisticated action is the reason so many professional pianists prefer the Model D: they feel at one with the instrument and believe that its range of tone and color brings out their musical best.

The Model D is the ideal piano for some–but not others

While the Model D has typically been associated with concert halls, an increasing number of Model Ds now find their way into homes.

In addition to the Model D being the overwhelming choice of professional concert pianists and universities worldwide, this 9’ grand piano is also appropriate for the home of both the professional pianist and the serious amateur.

However, the Model D is not the piano for the budget-minded or those with a modest living space. 11 feet of floor space in the home, including the bench, is needed to accommodate the Model D.

Model D’s cost

In essence, the Model D is for those who insist on the best possible piano–and who can afford its $198,400 price tag.

The concert grand of choice: a variety of Steinway Artists share their preference for the D

For five generations, Steinway & Sons’ Model D has stood out as the standard of the industry, the concert grand to which all others are compared. Today, over 95% of pianists performing with an orchestra request the Steinway Model D as their piano of choice.

Each generation of Steinway Artists has had champions for the Model D, pianists for whom the D was the piano that they had long sought as a performing artist. Several of these were at the very top of their profession. Some examples include:

- Sergei Rachmaninoff chose the Model D to record all of his sessions for Victor records.

- Vladimir Horowitz enjoyed “Beauty,” a Model D. When this piano was worn out, he had it rebuilt entirely.

- Glenn Gould liked his Model D so much that the jazz great had it sent to any venue where he was to play.

- Olga Samaroff purchased a ‘D’ for her Victor recordings. When the size of the D proved too large for storage, Samaroff parched a home with a studio large enough to accommodate the D.

- Elton John used the same Model D for hundreds of his concerts between the years 1974 – 1993. Among the concerts was the Live Aid concert held on July 13, 1985. An estimated 1.9 billion people, about 40% of the world’s population, heard Elton John’s Model D.

Play the choice of performing artists, universities, and music venues yourself

The materials and design Steinway & Sons have invested in the Model D is a testimony to company founder Henry Steinway’s famous philosophy to simply build the best piano possible.

Many believe Steinway has achieved that musical quest in developing and refining the Model D concert grand over five generations.

The combination of using the highest quality materials, creating the best possible design, and seeking input from the world’s greatest performing pianists have resulted in an exceptional 9’ grand piano.

The Model D is seen as the pinnacle of pianos for concert halls as well as the homes of all those who share Henry Steinway’s search for the perfect piano.

If you’re in the Greater Boston area, come into one of our showrooms and see for yourself the concert grand the musical world has been buzzing about for over 130 years: Steinway and Sons’ Model D.

Meantime, read further about what places Steinways in a class of their own:

- Steinway Model B Review: Is the B the perfect piano?

- Steinway vs. Bosendorfer: Which is the better piano for me?

- Do I need a Steinway if I’m not into classical music?

Steinway’s Model D: The iconic concert grand piano of choice

Steinway’s Model D: The iconic concert grand piano of choice

Steinway Model B Review: Is the B the perfect piano?

Steinway Model B Review: Is the B the perfect piano?

How to move a piano: Professional piano movers are best

How to move a piano: Professional piano movers are best

Boston vs. Yamaha: Which is the best piano for me?

Boston vs. Yamaha: Which is the best piano for me?

Steinway vs. Bosendorfer: Which is the better piano for me?

Steinway vs. Bosendorfer: Which is the better piano for me?

Digital vs. acoustic pianos: Which is the best for me?

Digital vs. acoustic pianos: Which is the best for me?

Spirio vs. Disklavier

Spirio vs. Disklavier